Three billion North American birds have disappeared since 1970. Audubon’s strategic plan, Flight Plan, outlines a plan to "bend the bird curve," meaning working to stop and eventually reverse the decline of birds across the Americas. Since birds know no borders, the effort must be hemispheric, from boreal Canada to the tip of South America.

Tracking the seasonal movements of migratory birds is a vital step toward understanding the full annual cycle and hemispheric conservation. Audubon’s Migratory Bird Tracking Program coordinates and supports tracking efforts throughout the organization to ensure alignment with the Flight Plan. The program involves people in identifying and tackling the factors causing bird population declines, providing crucial information to help reverse the decline. It will also offer resources and guidance to ensure that tracking efforts across Audubon grow to meet larger conservation challenges.

Menunkatuck Motus Station at the Sound School Photo: Bill DeLuca/Audubon

Since its installation a year ago, our Menunkatuck Motus Station at the Sound School has contributed to our understanding of bird migration by detecting eleven radio-tagged birds, including Ovenbirds migrating from as far away as Jamaica and Short-billed Dowitchers tagged in Delaware Bay during their northward migration. We are literally connecting the dots across the Western Hemisphere.

The Short-billed Dowitcher with Motus ID 64650 has a travel history that highlights the incredible endurance of shorebirds and the importance of the Atlantic Flyway.

Based on the Motus tracking data, here is the story of its journey:

1. The Beginning: Tagging in Delaware (May 2025)

Red knots and other shorebirds stop over in Delaware Bay to gorge on horseshoe crab eggs (Photo by NJDEP Fish & Wildlife)

Short-billed Dowitcher Delaware Bay: Cathy Ryden/Wash Wader Research Group

The journey of this specific dowitcher began on May 17, 2025, when it was captured and tagged by researchers at a critical stopover site in Delaware Bay. During this time of year, Delaware Bay is a "fueling station" for thousands of shorebirds that feast on horseshoe crab eggs to gain the weight necessary for their final push to the Arctic. [IMAGE}

2. Northward Sprint (Late May 2025)

After bulking up, the bird headed north. On May 30, 2025, its signal was picked up by the Motus tower at the Sound School. This detection provided a "snapshot" of its migration: it was moving quickly along the coast, likely flying under the cover of night or at high altitudes, using the coastline as a navigational guide.

3. Breeding in the Boreal Forest (June 2025)

The bird continued its journey to its breeding grounds in the Canadian Arctic/Subarctic, specifically the remote boreal wetlands where the forest meets the tundra.

The Nesting Cycle: Short-billed Dowitchers have a very tight breeding window. They incubate their eggs for about 21 days.

The Early Exit: In a fascinating quirk of this species' biology, the females often depart the breeding grounds almost immediately after the eggs hatch, leaving the males to finish raising the chicks.

Short-billed Dowitchers, juveniles, above the coast of Hudson Bay in Ontario, Canada, August 18, 2024. In northern Ontario, the Omushkego Cree are leading an effort with partners, including National Audubon Society and Wildlands League, to establish an Indigenous-led National Marine Conservation Area (NMCA) that would protect 35,000 square miles of Weeneebeg (Cree for James Bay) and Washaybeyoh (Hudson Bay) from oil and gas exploration, mining, ocean dumping, and industrial fishing. Photo: Sydney Walsh/Audubon

4. The Return South (July – August 2025)

By late summer, the bird was already heading back south. It was detected again in North Carolina, specifically at Lea Island and Pine Island Audubon Sanctuaries.

A Long Rest: While its northward journey was a sprint, its southward journey included more significant "layovers." In North Carolina, the bird was recorded hanging around for 27 days. This suggests these undeveloped barrier islands are vital resting spots where birds can recover from the 2,000-mile flight from Canada before continuing toward wintering grounds in the Caribbean or South America.

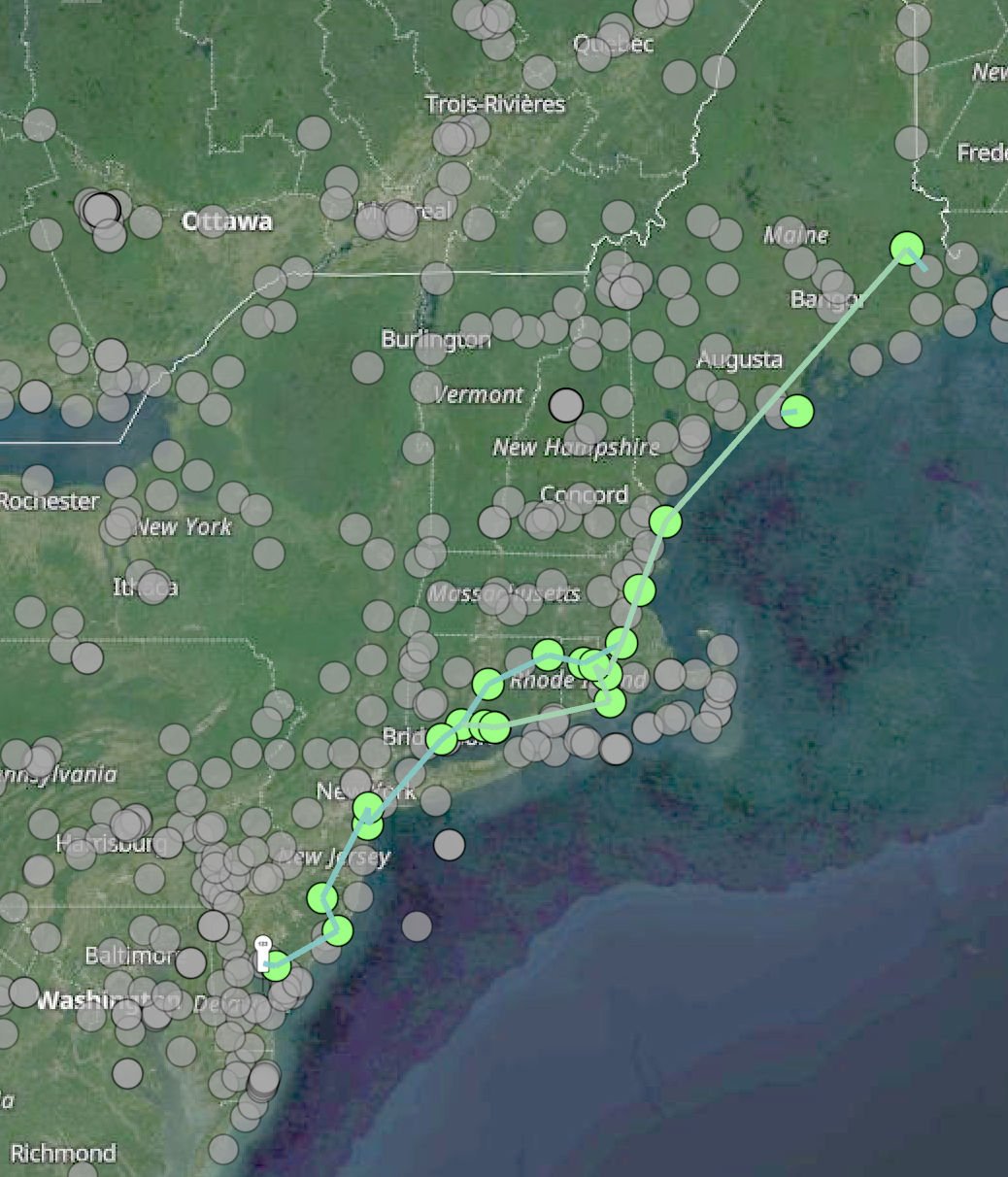

Short-billed Dowitcher (Motus ID 64650): The tracks you see on the Motus dashboard represent the "shortest possible path" between these detection towers. In reality, the bird likely followed the contours of the coast and the weather patterns of the Atlantic. (motus.org)