Each year, billions of birds undertake incredible journeys—some traveling thousands of miles from their breeding grounds to wintering sites and back again. These migrations are among the most remarkable phenomena in nature, but they are also among the most vulnerable. Along the way, birds face numerous challenges: shrinking stopover habitats, storms, predators, collisions with buildings and towers, and the increasing effects of climate change.

If we are to protect these species, we must first understand their migration patterns, destinations, and survival needs. That’s where the Motus Wildlife Tracking System comes into play.

The Motus Wildlife Tracking System has revolutionized the study of bird migration by using tiny radio transmitters, or nanotags, to track individual birds as they move across a network of receiving towers.

Motus (“movement” in Latin) is an international collaborative wildlife tracking network built to track migration and movements of birds, bats, and even large insects using automated radio telemetry.

Motus locations. Photo: motus.org

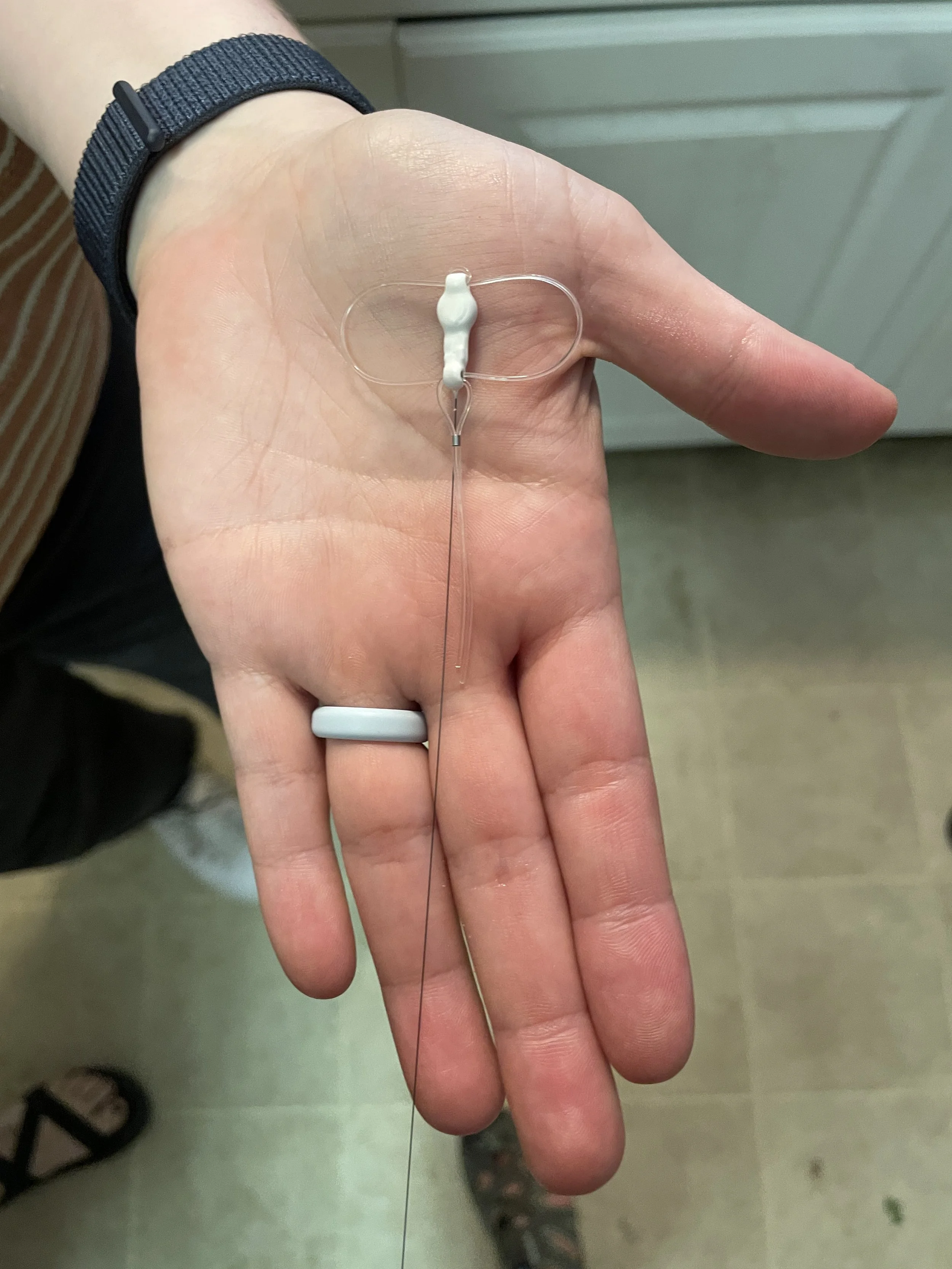

Motus nanontag: Sharon Audubon Center

Nanotags are very small, lightweight radio transmitters that emit a uniquely identifiable radio signal (“ping”) periodically. Because they are lightweight, they can be put on small animals, including small songbirds.

Motus nanotags are designed with bird safety in mind, but like any tracking device, they pose some risks. Researchers follow strict ethical and technical guidelines to minimize harm, and in most cases, the risks are very low compared to the scientific benefits of the data collected.

Motus tower at the Sound School in New Haven: Bill DeLuca?Audubon

Motus towers are ground-based receiving stations with antennas tuned to detect signals from nanotags when a tagged animal flies within range, typically about 15 km (9 miles).

When a tagged animal passes near a tower, the tower detects the tag ID and time of detection. The data are uploaded to the Motus database, where researchers from many organizations can access them.

Audubon and its chapters and partners have adopted Motus and nanotag tracking to better understand migration in ways that were previously impossible.

Audubon teams use nanotags on particular species of concern — ones that are declining or whose migration behavior is poorly understood, for example, the American Kestrel and songbirds like the Wood Thrush and Chimney Swift.

Information from detections at various towers helps us understand migration timing (when birds leave/arrive), stopover behavior (where they rest and refuel), and routes (which paths individuals take).

By inserting towers in areas that were poorly covered before, Audubon is helping close geographical gaps in the migration tracking network (interior areas, flyways, stopover habitats). This allows us to identify where habitats are utilized by migratory birds and where habitat protection or restoration would have the most significant impact.

Data is used to create interactive maps, such as the Bird Migration Explorer, allowing the public, policymakers, and conservation planners to visualize patterns.

Unlike banding, where you often need to recapture a bird (which may never happen), or geolocators that only store data until recovery, nanotags and towers enable automatic detection of movements.

There are limitations to the Motus tower data. There remain areas without receiving towers, so tagged animals flying through those regions might not be detected. Nanotags are another limiting factor with battery life and tag range being technical constraints. One of the biggest challenges for Motus is that only a small fraction of the billions of migrating birds are ever tagged. Tagging more birds would improve the Motus network's power, accuracy, and usefulness for conservation. Each bird with a nanotag not only helps protect its own species but also supports millions of other migrants sharing the skies.

Migration is risky, with many birds dying along the way. However, a nanotag on a bird that dies during migration can still provide highly valuable information—sometimes even more than one that completes its journey. Here’s the kind of valuable data researchers can gather:

If a tag signal stops moving but keeps transmitting from the same location, researchers can roughly identify where the bird died. Mapping these spots across many individuals can reveal “danger zones” along migration routes, such as areas with high collision risk or regions with habitat loss where birds are unable to refuel.

The moment a tag stops moving can show when a bird died—during departure, en route, or near its destination. Early losses might signal breeding-ground threats. Mid-migration deaths often indicate weather-related issues, exhaustion, or a lack of suitable stopover habitat. Late-stage losses may be related to wintering habitat conditions.

Every nanotagged bird, even one that doesn’t survive, becomes a messenger. Its final signal tells scientists where migration is breaking down—and that knowledge is precisely what’s needed to make migration safer for future generations.

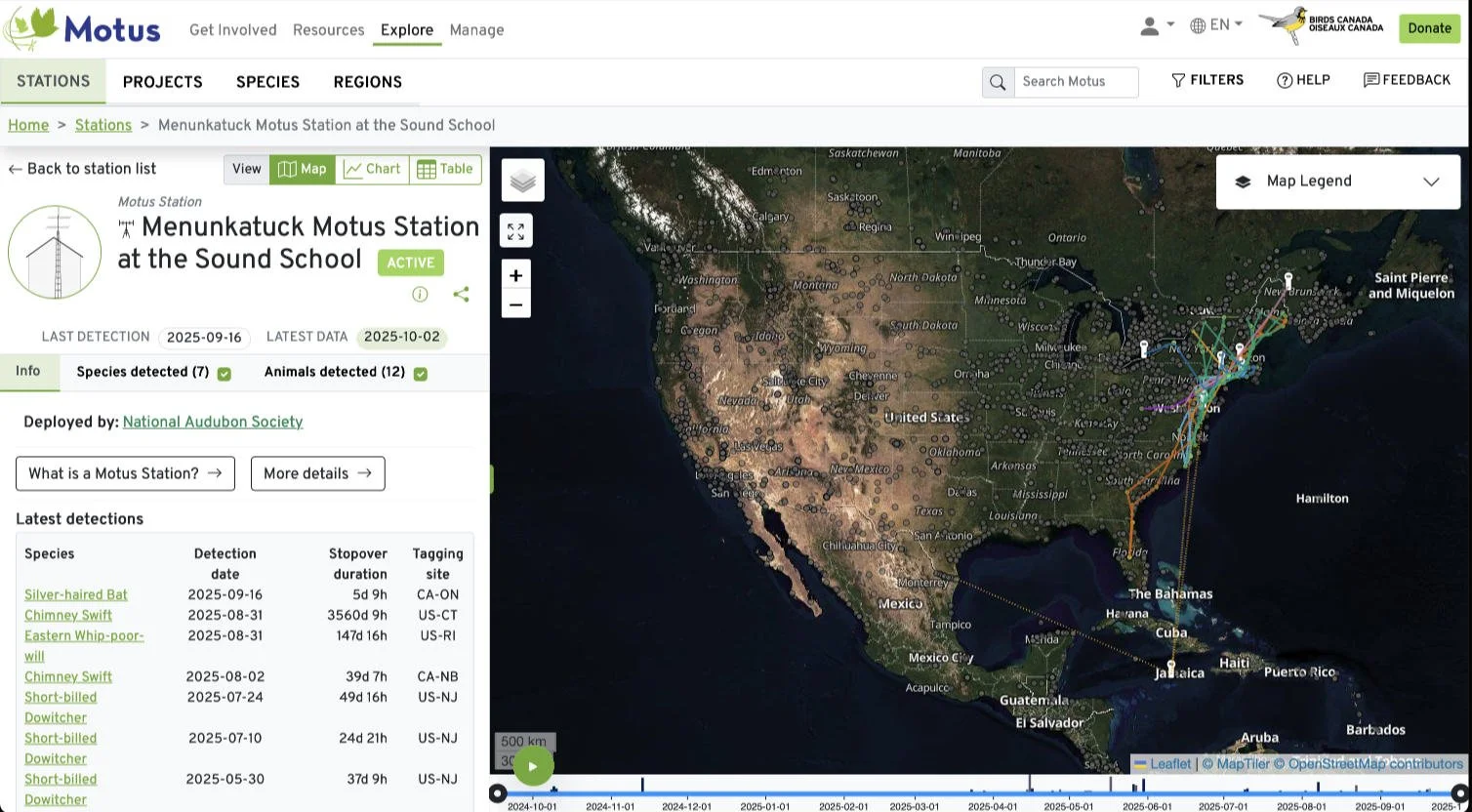

Menunkatuck Motus Station at the Sound School

A year ago, Menunkatuck and Audubon installed a Motus tower at the Sound School in New Haven.

Short-billed Dowitcher

Over the past year, the Menunkatuck tower has been pinged by several migrating birds. A Short-billed Dowitcher, which was captured and tagged at a stopover site in Delaware Bay on May 17, flew past New Haven Harbor on May 30. It continued north to its breeding ground in the coastal regions of the Canadian Arctic, where the boreal forest meets the tundra. Short-billed Dowitchers have a three-week incubation period, and shortly after the eggs hatch, the females depart to begin their southward migration. The bird that pinged New Haven in May pinged again on July 10 before continuing its journey south.

Chimney Swift

Chimney Swift with nanotag: Sharon Audubon Center

The Sharon Audubon Wildlife Rehabilitation Center treats hundreds of sick, injured, and orphaned birds and other wildlife each year. This year, the center rehabilitated 20 Chimney Swifts. Before they fledged, they were equipped with Motus nanotags as part of a project to track 20 rehabilitated Chimney Swifts from Sharon Audubon Center. The project aims to address two main goals: (1) improve our understanding of swift movements outside of the breeding season, and (2) evaluate the effectiveness of swift rehabilitation efforts by estimating seasonal survival.

On August 30, one of the swifts pinged the New Haven tower. It spent a day in the area and left on August 31 to continue south and was next recorded at the Natural Lands Gwynedd Preserve outside Philadelphia.

Other birds that have pinged the Menunkatuck tower include an American Woodcock, an American Kestrel, an Eastern Whip-poor-will, two other Short-billed Dowitchers, two Ovenbirds, and another Chimney Swift.

How to view the Menunkatuck Motus Station at the Sound School

Once on our station's page, you can scroll down to see all the birds that have passed by our tower. Birds only need to fly within 9 miles of the tower to be detected and appear on our station page. You can view specific details about each of these birds, including the date and location of their tagging and how many Motus towers they've flown past.